Policy makers worldwide have acknowledged the regulatory hurdles linked with the digital revolution, and have adopted various approaches in response, ranging from cautious observation to proactive experimentation to outright prohibition of some business models. If Governments continue shifting from ‘reactive’ to ‘proactive’ regulation to keep up with the pace of innovation and technology, the regulatory sandbox will become a standard tool that allows to innovate, test regulations, but also learn from the implications of technology and derive better regulations.

Since 2016 regulatory sandboxes have been used to promote fintech technologies and have spread globally to about 60 countries. The concept has recently expanded to other sectors, including healthtech, insurtech, Regtech, Govtech, Miltech (e.g. see Canada’s example), responsible AI and augmented reality, blockchain, 5G and 6G, and autonomous vehicles.

Several nations, such as Finland, Norway and the UK, have embraced the use of sandboxes to establish comprehensive legal frameworks for AI. This approach aligns with the EU’s perspective, which views regulatory sandboxes as catalysts for innovation and deems them essential for future regulatory endeavors concerning AI. This momentum has been further solidified by the European Commission’s incorporation of regulatory sandboxes into its Better Regulation Toolbox and their utilization in forthcoming initiatives like the pan-European blockchain sandbox and the AI Act (Article 53), aimed at fostering innovation and supporting SMEs.

So, what is a regulatory sandbox?

A regulatory sandbox entails a form of regulatory relief or flexibility granted to businesses, allowing them to experiment with new business models under reduced regulatory requirements. It typically incorporates measures to ensure overarching goals such as consumer protection. Functioning as a controlled environment, a regulatory sandbox enables companies to trial new concepts, products, or services without immediately encountering the full weight of regulatory obligations.

Due to its novelty, there is no universal agreement on the precise definition, resulting in a variety of interpretations and meanings. Nevertheless, distinguishing between relaxed regulation and regulatory leniency is crucial because regulatory “loopholes” are transient rather than permanent. It’s imperative to establish a defined timeframe and limit for the tests to ensure that experiments are conducted within a specific duration.

Although approaches to regulatory sandboxes may vary, they commonly share certain features: they are temporary, typically lasting up to six months for testing; they facilitate collaboration between regulators and firms; they waive existing legal provisions and offer tailored legal assistance for specific projects, often through trial and error; and the collection of technical and market data enables regulatory bodies to evaluate the suitability of existing legal frameworks or the need for adjustments. The design and implementation of regulatory sandboxes necessitate comprehensive planning and testing, employing robust methodologies and assessment frameworks to evaluate feasibility, demand, potential outcomes, and unintended consequences.

Regulatory sandboxes entail an “interest in regulatory discovery”. This means that the focus is not only on the innovation, but also on the question of what the legislature can learn for future legislation. Regulatory sandboxes will only result in better regulation if they involve a process of regulatory discovery. Interestingly in this context, the evolution of the regulatory sandbox reflects a broader shift in regulatory thinking. Instead of the traditional roles of government and reactive regulation, where rules are formulated in response to progress, we see a move toward proactive regulation, where regulators anticipate change and create flexible environments to understand and shape future innovations or technologies.

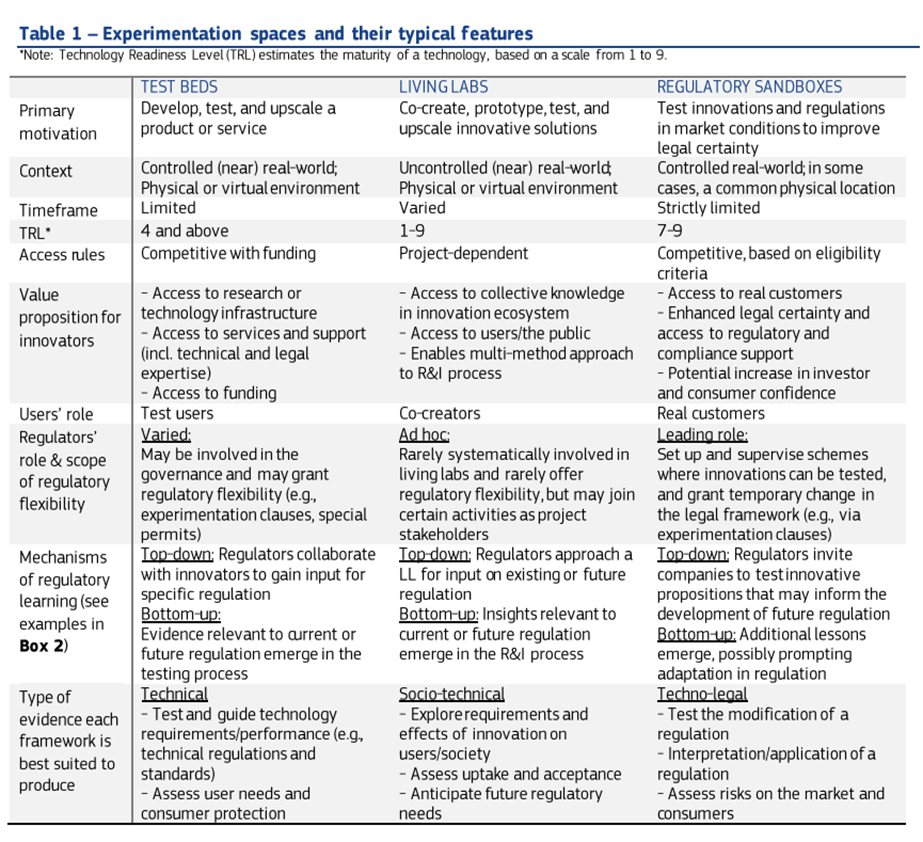

Regulatory sandboxes distinguish themselves from testbeds, innovation hubs, or living labs, yet they also exhibit some resemblances as they all serve as spaces for experimentation (refer to the table below).

Source: Kert, K., Vebrova, M. and Schade, S., Regulatory learning in experimentation spaces, European Commission, 2022, JRC130458.

Impact: the evidence so far

When it comes to impact, the largest body of knowledge is known about fintech technologies, and the impact of fintech regulatory sandboxes can be summarized as follows:

- Assisting policy makers’ decisions and regulatory change: Early evidence suggests sandbox programmes can result in regulatory change. Sandboxes facilitate open engagement between regulators and innovators. They are useful for testing innovations where empirical evidence is needed for policy development, and beneficial where regulatory requirements are unclear or create disproportionate barriers.

- Benefits for regulatory institutions: Sandboxes increase understanding and capacity to regulate fintech innovations, they test existing policy frameworks against new technologies and business models, build internal capacity and strengthen dialogue with the industry. For instance, in the banking industry, the sandbox may result in amending the rules on identity verification without a face-to-face meeting in certain circumstances.

- Financial inclusion: Limited evidence suggests sandboxes linked to financial inclusion mandates can reduce barriers, and properly implemented sandboxes can impact the broader financial system.

- Assisting private sector firms: Participation in sandboxes can facilitate market access for regulated and unregulated firms. Some firms experience reduced time to market through sandbox participation.

- Enabling market development: Strategic framework alongside fintech-driven initiatives enables innovation (creates markets for innovation). Sandboxes provide valuable insights for policy makers and promote innovation through gap analysis and open dialogue.

- Improved consumer protection: while sandboxes provide leeway for innovators, they are not a free ride. Regulators enforce strong consumer protections to ensure end users are not exposed to unreasonable risks.

- Fostering partnerships in the market: Sandboxes attract and develop marketplace partnerships and investors. Design features like partnership requirements and association with industry accelerators encourage partnerships.

- Strengthening competition: Mixed results have been found in increasing competition in the markets. Sandboxes may lower barriers for smaller firms but create an unequal playing field.

- Attract investment: A conducive regulatory environment can make a region or country more attractive to investors. Sandboxes signal a progressive attitude toward innovation and often attract venture capital and other investments.

Challenges and risks

At the same time, implementing a sandbox can pose risks, particularly when poorly considered and implemented. It can potentially pose unexpected burdens on the regulators and promote risks such as creating unlevel playing fields in the market. Regulatory sandboxes must evolve quickly to remain relevant. If the development of sandboxes lags behind technological advances, their effectiveness diminishes. This is particularly challenging, as regulatory decision-making processes often take longer. At the same time, experts have alerted to the potential negative impacts on consumer protection brought about by this ‘race to the bottom’ in the fintech sector. Regulators may prioritise innovation over putting adequate safeguards in place to protect the public and consumers.

Countries that find themselves with fewer resourced regulators may find it more challenging to replicate a sandbox approach, and a sandbox in such jurisdictions may be less appropriate. Before embarking on creating a regulatory sandbox, authorities should step back and objectively review the environment in which they operate, specifically by considering their primary objective(s) and relevant design considerations. Furthermore, a risk of fragmentation of the EU single market has been pinpointed if the testing parameters in a regulatory sandbox diverge significantly in different Member States. For companies operating across borders, navigating multiple sandbox environments in different jurisdictions can be complex and challenging.

Design considerations and principles

Although each sandbox has its own particularities depending on the sector and region, there are some universal considerations that need to be considered when setting them up:

- Objectives and Scope: It is important to clearly define what are the objectives of the Sandbox. Whether the goal is to promote fintech solutions, support green technologies, or explore novel healthcare interventions, this clarity will influence every other aspect of the planning, or loopholes will result. A central aim of the companies and research establishments engaged in regulatory sandboxes is to trial new technologies and business models in real life. In many cases, the focus is on the responses from the users and the markets, and on how well the innovations work. Aspects of public acceptance can also be of interest.

- Tailored regulatory environment: At the heart of the Sandbox is a tailored regulatory framework. This framework can include waiving certain requirements, aligning standards, or granting temporary licenses that allow innovators to test without facing the full regulatory consequences. One of most important benefits is the quick spread of regulatory learnings, both among regulators, but also firms who are keen to benefit from the experimentation of their peers. By regulatory learnings I mean anything from an approach to a new technology to the identification of unnecessary regulation that hinders innovation. This is important because recently there have been instances of policy instruments labeled as sandboxes where the potential impact of experimentation on regulation has not been carefully considered.

- Resource intensiveness: Sandboxes are highly resource intensive, and different governance models have been adopted for running them. The two most common approaches are the “hub-and-spoke” model or the dedicated unit. No set-up is ideal, however, and it is likely that not all the expertise necessary to review applications and support firms through testing will be available from a single set of resources.

- Multi-stakeholder collaboration: Open channels with industry experts, academics, and the public can enrich the sandbox experience. Especially the AI products and services are complex and often affect several areas, so several regulatory authorities must be involved in their testing. (In addition, Regulatory authorities need AI technical expertise to make decisions about access to sandboxes and to develop testing frameworks). This collaboration can provide additional insights and foster a holistic development environment. For example, in Germany, to achieve this, a Regulatory Sandboxes Network has been set up the, which now has some 400 members.

- Eligibility of participants: there should be a set of criteria that define who can apply to use the sandbox. These criteria may be based on the novelty of the innovation, potential market impact, or compliance with specific regulatory objectives. In addition, since participants often participate in sandbox experiments for financial support, the extent to which barriers to entry should be created there should be considered.

- Testing durations and parameters: Innovations need to undergo testing within a defined timeframe. Clear guidelines on permissible activities are essential to maintain the sandbox’s focus and relevance. If the duration is too short, measuring results may be challenging, while an overly long duration could lead to regulatory gaps favoring participants in the long run.

- Synergies – a strategic blend of tools targeting the entire ecosystem: Adopting a strategic mix of tools to facilitate innovation is considered the optimal approach, where regulatory sandboxes constitute just one component. For instance, in 2019, the UK Civil Aviation Authority launched an Innovation Hub and a regulatory sandbox specifically tailored for AI innovations. This integration of innovation hubs with regulatory sandboxes has been proposed as a solution to address scalability issues. Moreover, leveraging various anticipatory regulation tools is seen as highly advantageous for further establishing and advancing the Innovation principle.

- Consumer protection mechanisms: Even within a flexible regulatory environment, safeguarding consumer interests is imperative. Risk mitigation protocols, disclosure standards, and compensation mechanisms for adverse outcomes must be established. It should be transparent which key performance indicators (KPIs) are employed and how risks are assessed.

- Data management and privacy: In an era where data holds significant importance, ethical and secure handling of all sandbox data is crucial. While states require data and outcomes for informed regulation, exploring specific provisions for anonymizing and safeguarding data, along with protocols for data breaches, is essential.

- Continuous monitoring and evaluation, and post-testing paths. First, a continuous feedback loop is critical to the success of the sandbox. Regular insights from participants enable iterative development that ensures innovations align with market needs and regulatory standards. Second, the sandbox should be reviewed regularly, with clear metrics and monitoring and evaluation responsibilities. This ensures that it remains relevant and effective, and keeps pace with evolving industry dynamics. Test scenarios, special surveys, continuous measurements, and even “suprise check-ins” should be scheduled. Finally, once testing is complete, there should be clear paths for transition. This could mean transitioning the project to full market operations, requiring another iteration, or even discontinuing, or to what extent the data and results flow over into future regulations.

Conclusion

The future of sandboxes lies in the adaptability and potential of these frameworks to quickly adapt to challenges and to transfer value into the real economy. Sandboxes are relatively new regulatory instruments and have only been in operation for a few years; hence, results are still developing. When properly designed and implemented, they can be useful tools that provide valuable insights into new tech, but they are not the only mechanism that policy makers can use to foster innovation. As with any powerful tool, there are many difficulties in implementation.

First, regulatory agencies should avoid having a sandbox simply for the sake of having a sandbox. Launching and running a sandbox is no small undertaking. It requires a lot of learning and consumes human and financial resources. There are benefits to benchmarking against successful sandboxes globally. By incorporating best practice principles (as discussed above) and learning from the experiences of others, the sandbox can develop a more refined and effective operating model. However, this can be quite a challenge, considering that different countries are competing to offer the best conditions for innovators, and many want to be the first with their sandboxes for emerging tech.

Second, regulatory agencies should not view sandboxes as the sole or even the main avenue to encourage innovation. A flexible regulatory regime, where rules of the road are clear and regulators are willing to provide guidance when uncertainty arises, is the best mechanism for promoting innovation. Hence regulators should spend the bulk of their efforts on long term policymaking and rulemaking. The most a sandbox can do is provide temporary relief to a small number of market participants. Agencies should take advantage of sandbox experiments to design lasting policies that benefit the entire ecosystem. In addition, a holistic view is needed to design sandboxes as one of the tools in the strategic policy mix targeting the whole ecosystem of the emerging technology niche.

Photo: The “Sun and Sea” opera singers performing in Vilnius city

Literature

- Attrey, A., M. Lesher and C. Lomax (2020), “The role of sandboxes in promoting flexibility and innovation in the digital age”, Going Digital Toolkit Note, No. 2, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/data/notes/No2_ToolkitNote_Sandboxes.pdf.

- BEIS (2020) research paper on regulator approaches to support innovation (sandboxes as one example) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/regulator-approaches-to-facilitate-support-and-enable-innovation

- BMWi (2019) handbook for regulatory sandboxes: https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/EN/Publikationen/Digitale-Welt/handbook-regulatory-sandboxes.pdf%3F__blob%3DpublicationFile%26v%3D2

- EC Better regulation toolbox, Tool #22 includes regulatory sandboxes https://commission.europa.eu/law/law-making-process/planning-and-proposing-law/better-regulation/better-regulation-guidelines-and-toolbox/better-regulation-toolbox_en

- EC (2023) staff working document on regulatory learning https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-12199-2023-INIT/en/pdf

- ESMA (2018) report on fintech sandboxes: https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/library/jc_2018_74_joint_report_on_regulatory_sandboxes_and_innovation_hubs.pdf

- EP (2020) report on fintech sandboxes https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/f7485a21-084d-11eb-a511-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

- JRC (2022) policy brief on regulatory learning in experimentation spaces https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC130458

- Nesta’s work on innovation friendly regulation: https://www.nesta.org.uk/feature/innovation-methods/anticipatory-regulation/

- OECD (2023) Regulatory Sandboxes in AI: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/8f80a0e6-en.pdf?expires=1708430758&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=137CAB63579FDD2DCDF1606D78DDEB37

- Oeko-Institut (2021) Guide to design and evaluate regulatory experiments https://www.oeko.de/fileadmin/oekodoc/Regulatory_Experiments-Guide_for_Public_Administrations.pdf

- Yordanova K. and Bertels N. (2023) on Regulating AI: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-41264-6_23