Despite the variety of instruments to encourage business-science cooperation over the last decade, the results are not impressive. In response, recently there has been a general shift in the international science, technology and innovation (STI) policies towards mission-driven approach. Countries like Lithuania need to incorporate these developments nationally if they wish to design modern and effective STI policies and through that support various activities in the ecosystem, including business-science collaboration.

The traditional cooperation incentives are not delivering

A recent presentation on the efficiency of business and science cooperation in Lithuania concluded that although there is progress, but so far support measures following a targeted sectoral approach did not deliver substantial results.

Often the problem is that incentives to intensify industry-academia collaboration emanate from top-down policies formalized into laws that mandate ministries and their agencies to implement either functional (e.g. procurement) or thematic (e.g. specific areas deemed relevant) programmes. This approach is hampering cross-ministerial collaboration, it minimizes the ability of companies and other societal actors to define strategic areas and societal needs, and it may lead to an overly focus only on R&D as a source of innovation and competitiveness.

An emerging response – mission-based STI policy

In recent years there has been a clear pivot in different countries away from sectoral policies towards a ‘mission-driven approach’ to STI (also referred to as ‘vision- or challenge-driven policy’). This is not restricted to bringing together science and businesses but also embraces other system players, such as the public sector or not-for-profit civil society organisations, and makes provision to involve them more directly in STI activities. This approach is now firmly endorsed by the European Commission.

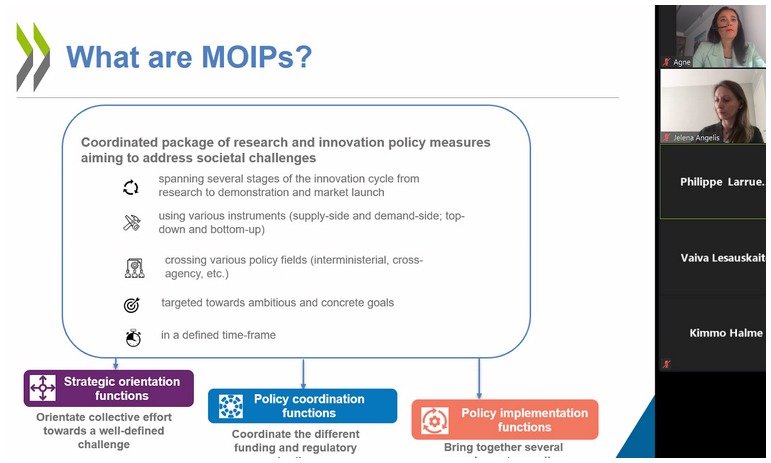

Missions are typically large-scale initiatives aimed at solving major societal challenges translated into concrete objectives and targets within a defined timeframe. Mixing the bottom-up and top-down processes, mixing policy measures, ensuring cross-disciplinary and cross-sectoral approached, cross-ministerial participation and involvement of a wider society are common elements in defining the missions towards the delivery on common goals. According to Mariana Mazzucato, who advised the European Commission on the introduction of missions into Horizon Europe, “missions provide a solution, an opportunity, and an approach to address the numerous challenges that people face in their daily lives”. The slide below depicts the OECD’s explanation of the mission-oriented innovation policies (from the discussion that took place in October 2020).

Mission-driven policy uses both top-down and bottom-up approaches to develop and communicate a clear high-level vision of STI’s role in dealing with economic, societal and environmental challenges. They are increasingly interdisciplinary in approach, including an extremely varied set of stakeholders, long-term in nature and focus more on indicators of impact rather than short-term outputs. While challenging to implement, they offer many advantages over traditional and more sector-focused STI programmes, and those countries experimenting with them have seen clear benefits. In particular, broadening participant involvement and encouraging cross-sector and interdisciplinary involvement offers increased opportunities for innovation to flourish. It also helps to overcome many of the barriers facing the research and higher education community as well as private sector, as captured above. The introduction of a mission-based approach to research and innovation, as advocated in the EU’s forthcoming Horizon Europe funding programme and seen in other countries, offers a welcome change of direction.

How to facilitate missions: examples from Europe

A review of recent experiences from Sweden, Ireland, and the Netherlands presents four types of support measures where a mission-, vision- or a challenge-based approach is applied. In October 2020 these approaches were discussed with the Lithuanian stakeholders from the engineering, food, life sciences and ICT sectors.

- Targeted instruments: An example from the Enterprise Ireland which introduced the Disruptive Technologies Innovation Fund not only to look for disruptive innovation solutions for the benefits of the Irish economy but also to bring a challenge-based approach to funding of projects.

- Vision-driven approach focused on specific sectors but encouraging cross-sectoral solutions: Vinnova’s approach for vision-driven innovation environments in Sweden is to use part of the funding to develop solutions to meet important health challenges by establishing five vision-driven innovation environments in the areas where Sweden has the greatest potential to make a difference.

- Conversion of sectoral research programmes into the wider Strategic Innovation Programmes (SIPs): SIPs in Sweden evolved from sectoral research programmes intending to promote competitiveness in sectoral areas to programmes which create preconditions for sustainable solutions to global societal challenges.

- Sector-specific PPP solutions combining both ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ approaches: The Top Sector approach in the Netherlands emerged from the desire to use regular financing to encourage public-private partnership, to reduce fragmentation in innovation policy, to increase the involvement of various ministries (rather than just the Ministry of Economic Affairs), and to create a shared vision within the triple helix.

Recommendations for policy action

A shift in STI policies towards a mission-driven approach would help Lithuania design modern and effective STI policies. This is a great opportunity for Lithuania to reinforce strategic orientation, tackle existing disciplinary, sectoral and policy silos, and encourage collective effort among different stakeholders as well as different policy-makers. This would also help to reinforce the culture of cooperation and co-creation – and not only between businesses and science but also bringing other stakeholders into the process. The recommendations below will set Lithuania on the road to a mission-driven approach to STI.

Apply mission-orientation to the national science and innovation policy

Five scenarios are proposed that allow the introduction of a mission-oriented approach to STI policy and the NSTPs. These scenarios are not necessarily mutually exclusive, can be combined, and can have differing degrees of ‘fit’ to the sectoral context and level of disruption to the status quo:

- Scenario 1: ‘Traditional’ science and technology programme (STP) with missions

- Scenario 2: A strategic umbrella NSTP based on the current set of instruments

- Scenario 3: A new strategic umbrella NSTP

- Scenario 4: Bringing existing instruments closer to missions

- Scenario 5: Challenge-based Innovation Fund

Scenario 1 envisages the introduction of a mission/vision to a traditional science and technology programmes. It largely builds on existing practice so no major changes to governance and implementation would be required. In Lithuania, it could be built on the existing ‘purposeful research’ programme. While the easiest to adopt, it is the least suitable to address the specifics and challenges of the ICT sector.

Scenario 2 envisages a strategic umbrella NSTP based on the current set of instruments. It would require the inclusion of new additional assessment criteria but pave the way for a smooth transition towards a mission- or challenge-based approach to STI policy and NSTPs. Scenario 3 envisages a completely new strategic umbrella NSTP created around missions or challenges. The main difference with Scenario 2 lies in the introduction of seed funding to support a fully bottom-up approach to the creation of missions and/or challenges. It would create a large-scale programme subject to constant monitoring. This scenario would require the most dramatic change in the current STI policy but would benefit all priority sectors.

Scenario 4 envisages bringing existing instruments closer to missions while Scenario 5 proposes the creation of a challenge-based Innovation Fund. These two scenarios are not directly linked to establishing an NSTP but are options for the introduction of a mission- or challenge-based approach to STI policy. Of the five scenarios presented here, Scenario 4 is likely to be the easiest to introduce and test but may not be a good fit for the engineering sector. Whereas the challenge-based Innovation Fund may not fit well with agro-food but is extremely favoured by the ICT sector.

Define missions through a combined top-down and bottom-up approach

To drive this process, different policy institutions including various thematic ministries, research councils and innovation agencies, should jointly agree on mission statements. It is critical to make this process as flexible as possible. The expectation should be that various national stakeholders (i.e. companies, research and education institutions, clusters, user groups, associations, science and technology parks) take up and co-develop these missions suggested by the policy-makers. This is needed to move away from a purely top-down approach, attract new types of actors and build new connections for delivering on missions which truly capture the needs and views of the whole community. In Lithuania, such a co-creation approach would also fit nicely into the recent strategies, such as ‘Lithuania Co-create’ and the National Development Plan that emphasise innovation as a horizontal priority.

Link missions with the smart specialisation strategy and priorities

At European level, a range of recent policy papers and reports have explored how to align future (2021-2027) smart specialisation strategies in terms of their contribution to meeting sustainable development goals, contributing to European-level missions (as defined for Horizon Europe), or to broader policy agendas such as the European Green Deal. This has led to a call for a shift in policy logic from S3 to smart specialisation strategies for sustainable and inclusive growth (S4). Mission-driven approaches that seek to address selected societal challenges can be the basis for identifying novel combinations of specialisations within an economy that are of a cross-sector and multidisciplinary nature, and for expanding the triple helix towards a quadruple helix approach.

Expand a list of beneficiaries in the support measures

The NSTPs and other support measures created around missions should take a broader approach to involving actors from the STI ecosystem when defining the list of eligible beneficiaries under funded programmes. Programmes that exclude the private sector or other stakeholders lack diversity and the critical momentum needed to innovate for economic or societal good.

Encourage cross-sectoral and cross-disciplinary consortia

Involving cross-sectoral, cross-actor, and cross-disciplinary teams in achieving a set mission offers several benefits, but introducing a new approach like this to the national STI system may also encounter difficulties in (a) getting a particular stakeholder group to join a project team, and (b) motivating the lead organisation to include teams from a variety of stakeholder types. To tackle these issues, incentives should be offered to encourage greater cross-sectoral, cross-actor, and cross-disciplinary involvement, and the matter should be reflected already in the call for proposal’s evaluation criteria.

Make monitoring and evaluation an integral part during the design and implementation

The long-term agendas set by mission-type policy interventions require well-structured monitoring and evaluation procedures that should be part of the initial roadmap design process. Each mission should be structured with respect to both a narrative vision (a statement of intent or objectives) and short-, medium- and long-term effects (targets, quantified to the extent possible) to be achieved by the interventions. Strategic reviews linked to additional rounds of funding should be performed periodically to provide a basis for a ‘go-no go’ decision by the programme management.

Reduce fragmentation and encourage pooling of resources

Different sectoral ministries are recommended to combine their funds through allocating a share of their procurement budget to co-funding the missions. The Government needs to incentivise ministries and agencies to cooperate, and develop a common language and strategy to implement a mission-based approach. For example, in Lithuania the basis for this has already been established by the National Council for Science, Technology and Innovation. They demand that, by 2030, at least 20 percent of all public institutions’ procurement budgets should go to innovative, pre-commercial procurement or ‘purposeful/on-demand’ R&D.

Don’t forget the old challenges!

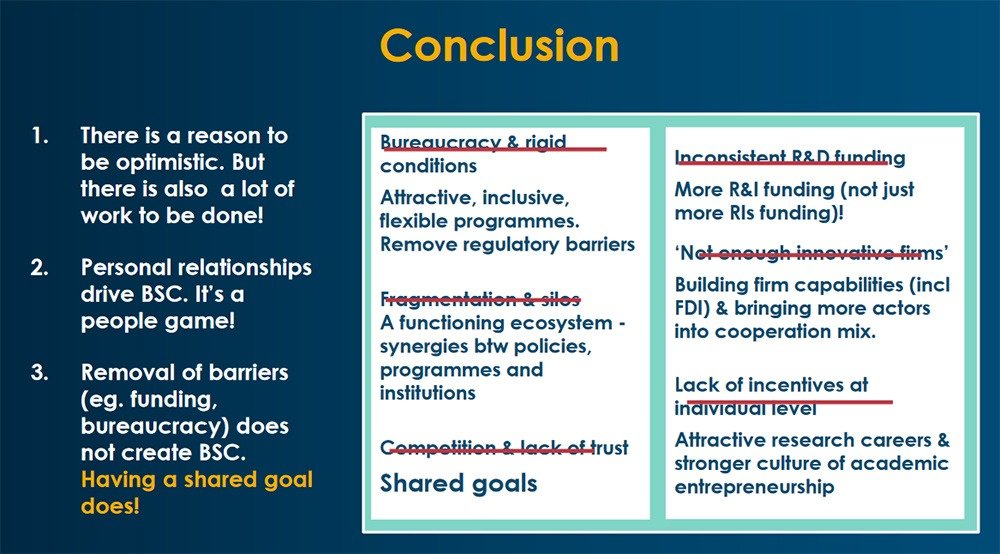

However, building new approaches on top of old approaches without solving the “old” problems may lead to even more fragmentation and wasted resources. In Lithuania, the key challenges are fragmentation, bureaucracy, inconsistent and unsustainable national R&D funding, and unattractive research careers, among others. The slide from my presentation below sums up the preconditions for building better business-science cooperation policies ready for the age of missions.

Source: Jelena Angelis, Lisa Cowey, Agnė Paliokaitė, Elžbieta Jašinskaitė, Alasdair Reid, Kimmo Halme (2020). Final Report. Enhancing the efficiency of the cooperation between business and science – Moving away from silos through a mission-orientated STI policy.

The project was funded by the European Union via the Structural Reform Support Programme and implemented by EFIS Centre and Visionary Analytics in cooperation with the European Commission’s Directorate General for Structural Reform Support and the OECD‘s team working on the missions based approach in Lithuania.

If you want to read more, follow the links: